Welcome to the second part of my Problem Solving series. How about you think about any problem you want to get solved right now? I will also think about one.

Welcome to the second part of my Problem Solving series. How about you think about any problem you want to get solved right now? I will also think about one.

But before we can start coming up with ideas for how to solve our problems, we need to know what the problem actually is to make sure, we don’t solve the wrong problem.

In the previous post, I defined a problem as something which when solved makes a situation better. I hope that makes sense for you, because if you wouldn’t believe solving the problem improves anything, then why would you want to solve it in the first place?

Problem Identification

My problem, right now is that it always takes me a long time to focus. If I cannot dedicate a block of at least three hours for writing, then I cannot get much done. Like this post.

In this context, I want to point out that there are two very general classes of problems. These are problems which either require:

- A return to a previous state, or

- A change from the current situation into a new state

Number 1 problems are broken machinery or equipment, processes that went out of sync, anything that stopped working the way it did. Simple examples can be:

- Damaged car

- Sudden communication problems in a previously well operating team

- A corrupt computer hard-drive

- Bodily injury

- Broken lamp

All these are problems with a clear problem statement: “Return to state at [insert date]”. Such situations require a specific discipline of problem solving, called troubleshooting. But more about that later.

I think you agree that my problem is obviously of the second kind. But what is my problem exactly? How about yours? Interestingly, most problems seem to be reduced to these three basic sources:

- Time

- Money

- Other people

If you agree, I have to disappoint you, but that is a false conclusion. It may be so because these are the things that trouble us the most. Maybe we like to relate a lot to either a lack of time or money or attribute to other people because all these seem beyond our immediate control. When we struggle to act it, is often because we position ourselves into a passive role.

Be the Active Part

If you take my problem, it seems to be time related. It is very difficult if not impossible for me to find these three hour blocks in my week. I could indeed say that time is my problem. But time is in reality, not the actual problem. I want to write, and I could easily write something in 30 minutes or less. It just takes me too long to “get into the zone”. That means I need to learn to be a productive writer even if I have much less than three hours.

In most cases, you can relate problems to some activity that cannot be done without solving the problems.

“I want to write”

Can you see the difference? I am now taking on the active part and thus show a propensity for action.

Take a broken lamp. Yes, you want to turn the lamp back on. But the actual action, for example, is: “I want to read when it is dark”. It is out of the question that you want to get your lamp fixed or replaced, but can you see how focusing on the activity shifts the attention away from the object to you as the active element? It also opens the view for different solutions.

Find the Core Problem

While preparing for the problem course series I jotted down all sorts of problems people would mention around me or in forums. One example that often came up was when someone wrote he or she would have to stop

- going to the gym

- buying fresh vegetables and fruits

- playing tennis

- going to the movies

- paying for golf lessons

- reading books

- etc…

because they don’t have the money anymore to pay for these things.

I have to mention that none of these people is going through extreme financial hardships. All these started doing something they seemed to like and could afford when they started, but stop doing it for financial reasons. In some cases, when someone offered solutions, the next thing was the lack of time or something else that prevented them from continuing. I guess you can see; these are likely just excuses because those activities don’t have the highest priority and these people don’t want to continue. It comes down to a priority issue and not a financial problem.

Going back to phrasing the problem as an activity:

“I want to learn to be a better golf player.”

This states the core of the problem, which really only becomes a real problem by adding the conditions that we often don’t spell out.

Determine Your Base Conditions

If you play often enough over a longer period of time, you’ll get better eventually. But of course you likely want to reach a certain level in a certain amount of time. These would be your two base requirements (or conditions) for considering your problem solved.

Your problem statement may now sound like:

“I want to be a handicap 18 golf player in one year.”

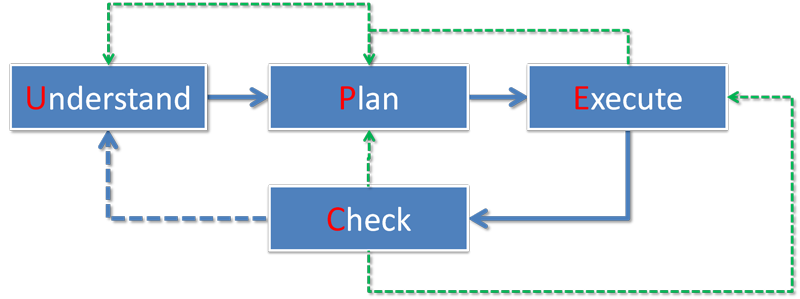

Whether this goal is realistic at all, should become obvious when you are in the planning phase of the UPEC Process. In that phase, you will also define your ideal (e.g. both base requirements met)outcome and your Minimal Acceptable Result (MAR). The MAR in this case may be reaching handicap 30 in one year.

Summary

Part one in understanding your problem is identifying your problem. You do that by following these steps:

- Find the core problem.

- Express it as an activity you want to do.

- Identify your base conditions.

- Phrase your problem statement including your base conditions.

If I do this for my example problem it could look like this

- Core problem: long “warm up” time

- Expressed as activity: I want to work with more focus.

- Base conditions:

- Get into “my zone” in 10 minutes

- by next month

- Problem statement: By next month I want to be able to get absolutely focused on any activity within 10 minutes.

You see; I could have written that I want to be able to write X many words in 30 minutes, but that is not my core problem. When I am in a good mood, I am able to write a lot in a short time. That is not where I am losing my productivity. Of course, your problem statement doesn’t need to be perfect. As you go through the UPEC cycle you can of course always take a step back and refine:

Don’t worry, I will bring some examples in the upcoming lessons.

Recognize Limitations and Other Factors

After this much thinking about your problem, this part should now be fairly easy for you. All you need to do before you can move to the planning phase is making a list with all the limitations and other factors you think will affect finding a viable solution.

Now, this could be the amount of time you think you can invest or the amount of money you want to spend to reach this new state. It could be obstacles like unsupporting family or team members. I wrote about a similar thinking in Know Your Starting Point. As I said, problem solving is like goal setting because you also want to reach a specific goal. With the difference that the how is not obvious for you at this point.

In my case such limitations and factors may be:

- My peak performance vs my “bad” times during the day

- General tight schedule

- Want to be able to post weekly

How about you complete these same steps for your problem? If you feel comfortable, you are invited to post them below in the comments for open feedback or can send them to me, and I will get back to you with my comments as soon as possible.

We are now ready to tackle the “meat” of problem solving: The idea creation process as part of the general solution planning phase.

The Problem Solving Series

So far these lessons of the Problem Solving 101 course have been published:

- Lesson 1: Introduction

- Lesson 2: Understanding Your Problem (this post)

- Lesson 3: Planing Solutions Part 1

- Lesson 4: Execute and Measure

- Lesson 5: The Big Why

- Lesson 6: No Checks, No Glory

- Lesson 7: Creating Ideas

- Lesson 8: The Value of Testing Everything

- Lesson 9: The Failure Game

[ois skin=”Never miss a new post”]